Sibudu Shelter

Sibudu Shelter, South-Africa

Bone tools for digging and debarking 80,000-year-old trees discovered in South Africa

An international team of archaeologists, including five researchers from the Major Human Past Research Programme at the University of Bordeaux, has just published the discovery of the oldest bone tools in southern Africa and proposes, based on new analytical techniques, that these tools were used for debarking trees and digging in the ground. The tools were found in the famous Sibudu shelter in the Kwa Zulu-Natal region, within several archaeological layers dated between 80 000 and 60 000 years ago.

The first bone tools

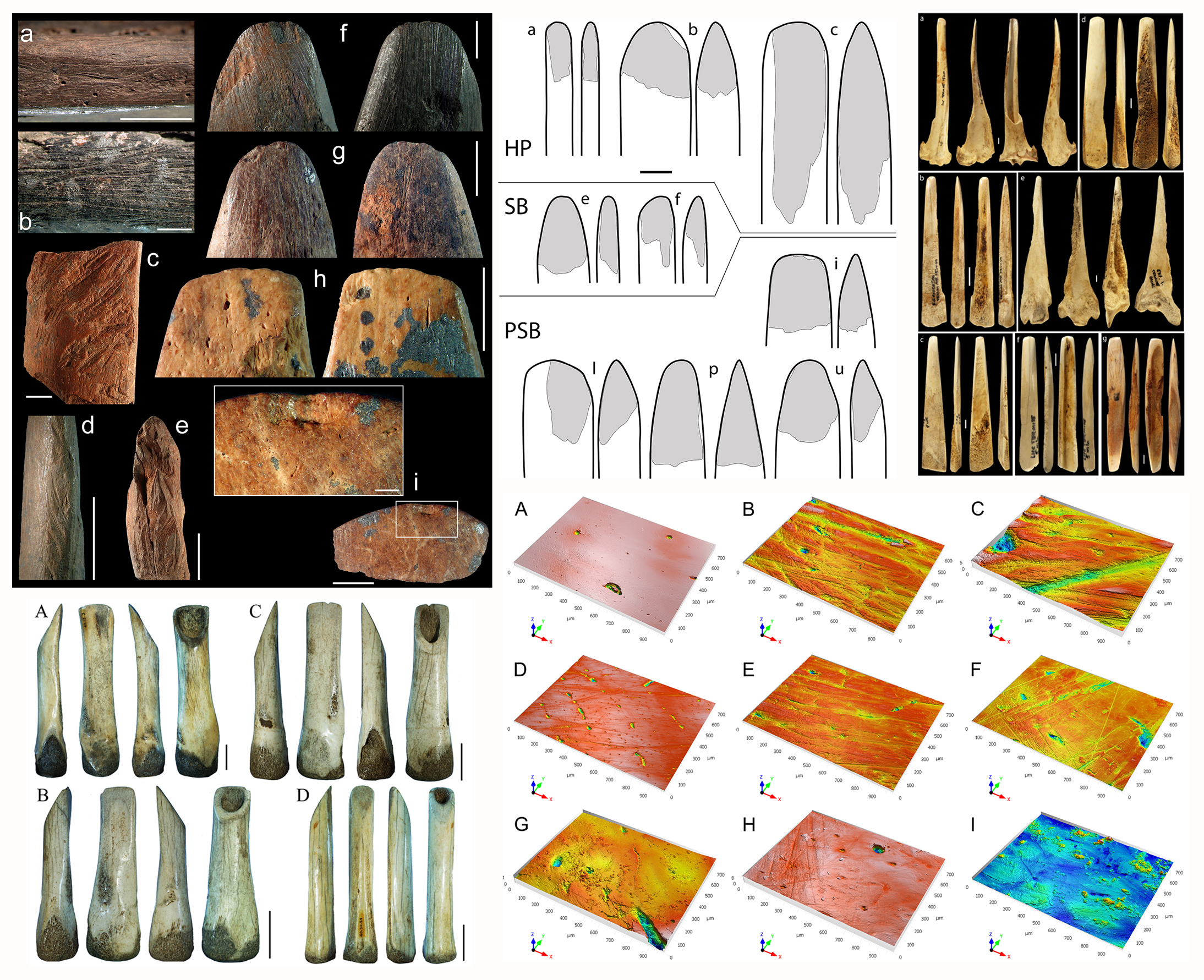

Our ancestors used bone fragments as tools as early as two million years ago, and evidence of bone cutting with techniques similar to stone cutting has existed for 1.8 million years. But when did bone tools appear that were fully worked with techniques adapted to the bone material, such as abrasion, scraping and grooving? The application of these techniques made it possible to determine the final shape and size of objects with a high degree of precision, to facilitate their fitting, but also to impose a style on them, thus making them emblematic of a human group. Until the beginning of this century, the application of these techniques was considered to be an innovation introduced into Europe around 40,000 years ago by modern man. Research over the last two decades has led to the discovery of fully fashioned bone tools in several parts of Africa, some of which may be as old as 100,000 years. While the objects discovered so far are rare or non-standard in shape, a new discovery, just published, changes the picture. The study describes 23 bone tools found in Sibudu, a rock shelter in the Kwa Zulu-Natal province of South Africa, in archaeological layers dating back 80 000 to 60 000 years. All of these objects are similar in shape, with a flattened, ogival-shaped end in particular.

The researchers did not limit themselves to reconstructing how the tools were made. They used a confocal microscope to measure, in three dimensions, the roughness of the areas worn by the work, both on archaeological tools and on ethnographic tools and, above all, for comparison, on reproductions of these tools, used experimentally. Several experiments were carried out for comparison with the archaeological material, such as debarking trees whose bark is still used today in Africa in the traditional pharmacopoeia, treating skins with and without ochre or digging in sediments inside and outside the cave. By applying a discriminant statistical analysis on these roughness measurements, they concluded that tree barking and digging in humus-rich soil are the activities that most closely match those recorded on most Sibudu tools.

The researchers note that this type of tool continues to be used at this site for 20,000 years, despite the fact that the occupants radically change the way they produce stone tools during this period. These results seem to support a scenario in which certain human groups in southern Africa developed and maintained specific, highly standardised cultural traits locally, while other manifestations of their material culture are shared widely across the subcontinent.

Reference

d’Errico, F., Backwell L.R., Lyn Wadley, L. Lila Geis, L., Queffelec, A. William E. Banks, W.E., Luc Doyon, L. In press. Technological and functional analysis of 80–60 ka bone wedges from Sibudu (KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa). Scientific Reports 12, 16270 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-20680-z

Researcher Contact

Francesco d'Errico, PACEA

Communiqué de presse en français

Dernière mise à jour :

Figure 1

Figure 2: